Searching the Depths

It’s tough to live in the ocean.

Its myriad creatures may start life as microscopic specks of plankton, at the mercy of battering currents and becoming another animal’s meal. As they grow, they might find an attractive bit of food is attached to an angler’s hook, or water conditions are uncomfortable because of pollution or climate change.

But there are people at CSULB who care about them. Being near the ocean made sense for the campus to create the first marine biology program in the CSU system and continues to make worldwide impacts.

By the Beautiful Sea

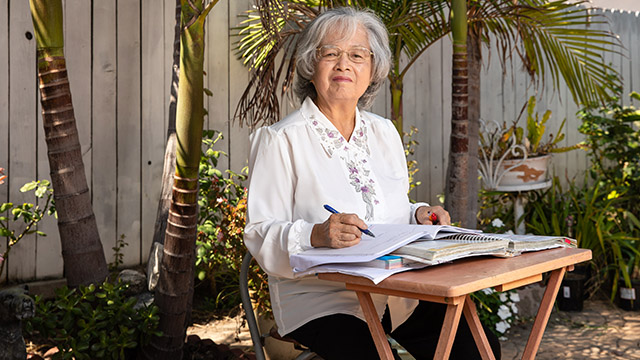

Before you bite into that fish on your plate, consider how it got there. It may have started life in the Bolsa Chica Wetlands in Huntington Beach or Long Beach’s Colorado Lagoon that serve as important nurseries for a host of marine animals and plants, which interest Associate Professor Christine Whitcraft.

“I say that we’re all things wetlands,” explained Whitcraft, who also is president of the Friends of the Colorado Lagoon and sits on the Bolsa Chica Conservancy board. “I collaborate a lot with Jesse Dillon on microbial community work, all the way up to large creatures such as working with Chris Lowe’s lab on fish and sharks. Really, the connection for me are the food webs in between those different levels, so I’m interested in connecting how microbial communities break down plant material and also support plants, then how invertebrates interact with microbes and plants, then how fish and birds feed on those invertebrates and so forth.”

Shoreline and marsh microorganisms are essential to the food web, said Dillon, an assistant professor. One of his local wetlands projects is looking at potential effects from sea level rise on marsh communities. He’s also interested in microbes that live next to small hydrothermal vents at White Point on the Palos Verdes Peninsula, so he and collaborators from Caltech and Washington University in St. Louis have a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to learn more about these organisms.

Creatures Small and Great

The colorful urchins, sea stars and snails along a rocky shore are lucky to be there at all, according to Assistant Professor Douglas Pace, an environmental physiologist.

“You can think of the ocean as this epicenter of bad parenting,” Pace said. “They’re fertilized in the water column and at that moment, they’re completely on their own and are taken away by whatever current they’re in and they have to solve every problem themselves. What I really want to understand is how do they deal with that? You have to find a way to hang on and deal with all these changing environmental factors and hope you arrive at the right place.”

Even reaching a suitable habitat doesn’t guarantee safety, so Associate Professor Bengt Allen and collaborator Mark Denny at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, Calif., have an NSF grant to study how flat snails called limpets that live in rocky intertidal areas deal with environmental changes.

“Under average conditions, organisms do just fine, but it’s the really hot day that makes you stressed or the really big wave that knocks you off the rock and kills you,” Allen said. “A lot of the climate models that we’re using currently suggest that, in addition to seeing changing average conditions, we should see increasing variability; more frequent hot days and more extreme wave conditions.”

One of their preliminary findings is that individual growth and survival are definitely linked to temperature variation and that the animals can cope better if they have good food resources.

Healthy larvae that drift in from elsewhere are also important to replenishing vulnerable communities; for instance, sea stars that are dying from a disease, said Professor Bruno Pernet, who studies marine invertebrates. “We’re really interested in how those larvae feed because that affects how much time they spend in the plankton and how far they disperse.”

By the Numbers

But if relatively few females produce most of the larvae, they can limit the population’s genetic diversity — a possible sign of overfishing or other environmental factors, which interests Professor Ray Wilson.

He’s looked at everything from invasive goby fish that came to San Francisco Bay in commercial ship ballast water to what kind of fish live deep in the Pacific and Atlantic. He’s even dived twice to about 10,000 feet in the central North Atlantic aboard the Russian MIR submersibles as part of an international research consortium. Lately, he and his students have studied genetic diversity in Dover sole and Pacific sanddabs, popular seafood from California deep slopes.

CSULB’s internationally renowned Shark Lab, founded in 1966 by the late Professor Donald Nelson, is now directed by Professor Christopher Lowe, an alumnus whose interests range from sharks and rays to understanding fish population dynamics.

With funding from organizations including Southern California Edison, NSF, NOAA and more, Lowe and his students are innovators in using technology to understand where animals are born and move, making the Shark Lab one of the largest telemetry labs in the country. This information is helping state and federal officials evaluate marine reserve areas and what to do with offshore oil platforms.

He’s even working with CSULB’s Mechanical and Aerospace Department to develop a small autonomous unit to study marshes, which also is useful for Whitcraft and Dillon; and autonomous hexcopters for aerial surveying of coastal shark populations.

Meanwhile, Assistant Professor Darren Johnson uses mathematical models to understand where animals are going and the rules they follow for moving around. “How are they going to respond to different changes in the environment?” such as seawater temperature or alkalinity, he wonders. He’s also looking at how kelp bass, a popular sport fish that preys on surf perch, has declined in numbers except in protected marine areas, and how that might affect perch populations.

Water Matters

Male fish with high levels of female hormones called estrogens are a fact off Southern California and elsewhere, but where these and other endocrine (hormone)-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) come from and their effects on fish has been the focus of Professor Kevin Kelley, now associate dean of research for the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

Thus far, he said, higher estrogens in males don’t seem to affect their reproductive ability, but some other EDCs appear to interfere with other endocrine systems (e.g., thyroid, stress responses). Many of these chemicals can make their way up the food chain when contaminants sink to the ocean floor and are absorbed by worms that then are eaten by bottom-dwelling fish.

Plant life is another indicator of ocean health, including kelp forests that are the research realm of Professor Steven Manley. He is creator of the Kelp Watch 2014/2015 project to track radioactive residue crossing the Pacific as a result of the March 2011 Japanese Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant tsunami damage, collaborating with Kai Vetter of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and other researchers.

Circle of Life

Preparing the next generation of biologists is just as important to the faculty. “Overall I think our program should be very proud of our graduates,” Whitcraft said. “I see them at Caltrans, Department of Fish and Wildlife, consultant companies, Sea Grant fellowships and all sorts of positions. We interact with them now as professionals. Ultimately, I think my best goal as a mentor is when I’m working with or competing for grants with my own former students, which I think is cool.”

Building the Future

Some of CSULB’s marine biology students and alumni include:

- Ryan Freedman, an M.S. student and 2014 California Sea Grant Fellow who’s entering the UC Santa Barbara Ph.D. program to study effects of marine protected areas.

- Kristy Forsgren and Erin (Misty) Paig-Tran, assistant professors of biological sciences at Cal State Fullerton. Forsgren is an expert in fish reproduction and Paig-Tran studies filter-feeding fishes, rays and sharks.

- Yannis Papastamatiou, assistant professor of biological sciences at Florida International University and a shark expert focusing on behavior. He continues to work with Lowe on shark research at Palmyra Atoll.

- Carlos Mireles and Heather Gliniak, marine biologists with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

- Elizabeth Duncan, an M.S. student who received an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship to support her thesis project studying effects of temperature variability on federally endangered black abalone.

- Julianne Kalman Passarelli, curator of exhibits and collections at the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, San Pedro.

- Jesus A. Reyes, president of the Pacific Coast Environmental Conservancy who took part in the 2014 Pacific Gyre Expedition that examined the mid-Pacific floating trash collection. He’s also endocrine analysis lab manager at CSULB’s Institute for Integrated Research in Materials, Environments & Society.

Did You Know?

A female great white shark gives birth to two to 14 five-foot-long live young hatched from eggs inside her. She also creates extra unfertilized eggs for the babies to eat in the womb.

To help avoid being stung by rays, shuffle your feet in the sand to scare them away.

A female sea urchin can release more than a million eggs, but very few survive to adulthood.